I never

thought that researching a postcard would lead to finding links (some tenuous)

between a piece of family land and Abraham Lincoln, the Franklin Expedition, the Red River Colony, the Oregon Trail and a postcard company, and myself to all

of them. But here it is. Written by Sandi Ratch on October 17, 2019 - a coincidence that I wrote it the same day Lincoln wrote something very important:

On October

17, 1863, Abraham Lincoln released a proclamation calling for 300,000 new volunteers

to join the United States army for three years or the rest of the war – the war

had started in April, 1861, and when Lincoln made the call for more men, the

expiration of the first volunteers’ three-years’ service was approaching. That same

day he also wrote a difficult reply to a request from Major General John Gray Foster,

declaring that Dr. David M. Wright would, indeed, be executed.

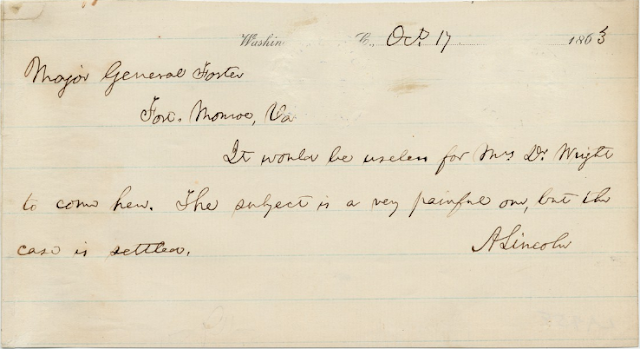

“Major General Foster

Fort Monroe, VA

It would be useless for Mrs.

D. Wright to come here. The subject is a very painful one,

but the case is settled. A

Lincoln.”[i][ia]

Three

months earlier, on July 11, 1863, Dr. Wright had been “nettling” Second

Lieutenant Alanson L. Sanborn, a white officer who was marching at the head of

his company, the 1st U.S. Colored Volunteers[ii],

along the main streets of Norfolk, Virginia. An altercation between the two men

led to Sanborn being shot dead. The two sides of the story are, of course,

both spun to an opinion: one stating that the Doctor had been defending women

and children from abuse by the soldiers and may not have actually levelled the

deathly shot;[iii]

the other stating that Wright, a “violent Secessionist”[iv],

had taunted the U.S. Army officer and then shot him after the threat of arrest.[v]

We’ll never know where the truth lies, but Wright was sentenced to death by a

special military commission[vi].

After the sentence, Lincoln postponed the execution until an insanity

examination could be conducted,[vii]

but Wright was declared sane at the time of the shooting by Dr. John P. Gray.[viii]

A petition signed by nearly 200 citizens of Norfolk was also written on October

17, 1863, but it did nothing to inspire Lincoln to commute Wright’s execution,

and despite two escape attempts in the following week,[ix]

Wright was hanged for the murder on October 23.[x]

Abraham Lincoln November 8,

1863 (Library of Congress)[xi]

Dr. David Minton Wright [xii]

On the

evening of October 17, Grover’s National Theater in Washington was presenting Lincoln’s

favourite play, Macbeth, starring Charlotte Cushman as Lady Macbeth [xiii, p.4].

“The most famous American actress of her generation and the most famous Lady Macbeth”[xiv, p.7],

Cushman was a woman before her time. Living in Rome to accommodate an

“alternate lifestyle”, Charlotte was a lesbian thespian from an old American

family. This evening’s performance was part of a 5 Yankee-city tour to raise

funds for the United States Sanitary Commission [xv].

The tour ended up contributing $8,000 toward the care of sick and wounded Union

soldiers [xvi, p.7]. President

and Mrs. Lincoln and presidential aide William O. Stoddard attended that

night’s performance.

Grover’s National Theatre in

Washington D.C. [xviii]

Despite the

busy and probably emotional activities of October 17, 1863, Lincoln also found

time to sign an Oregon land patent for one John Flett and the descendants of

his deceased wife, Charlotte (Bird) Flett.

John Flett

Flett was

born in August, 1815. A Métis member of

the Red River Colony (present-day Winnipeg), he was the son of a Scottish Hudson’s

Bay Company man (from the Orkney Islands, Scotland) and a half-aboriginal

mother. By the time he was 25, the

bread-and-butter beaver-felt hat had fallen out of style, being replaced by the

finer, less furry fibres of oriental silk – putting a strain on the Hudson’s

Bay Company and the fur trade in general.

By 1841, with the fur trade in a

rather precarious position, George Simpson (from Dingwall, Scotland), the

Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, had asked Chief Factor Duncan Finlayson

(from the Orkneys) to recruit settlers from the Colony to help maintain HBC control

of the northwest [xix]. Finlayson contracted with James Sinclair

(also the son of a Scottish man from the Orkneys – see a pattern here?) and 21

metis families (121 bodies in all) to make the long journey on foot and by Red

River cart from Winnipeg to Puget Sound in Washington Territory with the promise

of houses, barns, fenced fields and much livestock. John Flett (25 years old

and Sinclair’s brother in law) and his family (wife, Charlotte, and two

children) were part of that group and would end up eventually settling in the

Willamette Valley of the Oregon Territory. Pierre St. Germain was one of Flett’s

emigrant companions. Like the rest of them, Germain was Métis - and he had

exceptional survival skills which had aided him in becoming an interpreter on

the first Franklin Expedition to the Arctic.

He was “considered a rogue, a rebel, and a troublemaker by Franklin”,

but was nonetheless an indispensable, strong, versatile and resourceful servant [xx].

Someone I’m sure Flett appreciated as a travelling companion.

The

Sinclair expedition travelled from Red River to the Saskatchewan River, through

Fort Edmonton, and down to Rocky Mountain Fort. (As an aside, 139 years later,

Dr. David Burley, an archaeology professor from Simon Fraser University and

second on my graduate committee, would excavate Rocky Mountain Fort and remove

the old fireplace stones from it in the hopes of reconstruction in a museum. Sometime

around 1989, I would be tasked with cleaning and reconstructing those fireplace

stones - beside which Flett or his companions most likely warmed themselves).

The Sinclair Expedition then travelled through the Rocky Mountains to Canal

Flats[xxi],

past the future site of Fort Steele (where I would run an archaeological

excavation for 2 years in the late 90s), Tobacco Prairie, Lake Pend d’Oreille,

Fort Nez Pierce (Walla Walla) and on to Fort Vancouver. Things didn’t work out

for the party in Puget Sound – the promises had not been kept by the HBC and no

good future could be seen, so in 1842 Flett moved south to the Willamette

Valley in what would become the Oregon Territory. The population for all of the

Oregon Territory in 1850, when they first took a census, was 13,294 (which may

or may not have included the Aboriginal population).[xxii]

As a

married man, Flett had been allowed, by the Oregon-Donation Act, to claim 640

acres - he took 634.86. The land in question included three sections located on

Wapato Creek, just south of Wapato Lake (near the current community of Gaston,

which is north of McMinnville). Located in the west boundary area of the

Willamette Valley, the land was perfect for farming – low-lying fertile soils

for planting, and plenty of high grassy areas for raising cattle. Lots of

timber for building, and a seemingly endless supply of water. Residing on the

land from 1842 to 1859, Flett farmed and tamed that particular piece of

wilderness while also working as an interpreter between the local American

Indians and the government. His work included interpreting for General Joel

Palmer at the Walla Walla Council of June, 1855, and being instrumental in

treaty negotiations with a number of tribes following the Indian Wars of

1855-57. In 1859, Flett filed another claim in Pierce County, Washington

Territory, near the town of Orting and moved there. Sometime between 1879 [xxiii]

and 1928 [xxiv]

Flett or his descendants sold the Willamette Valley land, part of which ended

up in the hands of an immigrant son of a Scottish blacksmith.

Alexander

Steele (Uncle Alick) had moved to Oregon in 1908. One winter, likely between

1909 and 1913 [xxv],

he and his wife Nellie bought a postcard.

It was a colourized lithograph showing a mature apple orchard in Oregon with

holly berries in the background. All that is written on the back is “Just to

wish you a Happy New Year from Alick + Nellie.” His younger sister (also named Nellie, and my great-grandmother) would follow him to North America in 1912 fatefully

missing a voyage on the RMS Titanic and settling in Vancouver, British Columbia.

On the

back, the postcard clearly reads: “Patton Post Card Co., Salem, Oregon.”

The Patton

Brothers, Hal and Cooke, started the Patton Postcard Company in 1908. The men were

the sons of one successful Oregon Trail pioneer, Thomas McFadden Patton, and

the grandsons of another, Edwin. C. Cooke. The Oregon Trail had been forming

before the summer of 1843, but after that year, when the “Great Migration” of

some 700 – 1,000 emigrants headed west from Missouri to Oregon, the trail

became more permanent. Patton and Cooke, unknown to each other before the trip,

along with other settlers and uncounted men headed to California for the Gold

Rush, travelled the route in 1851. The 22-year-old Patton made it to Oregon, the

older Cooke was in poor health so he, his wife, and his 14-year-old daughter,

Frances (“Frank”) stayed in Salt Lake City for the winter. The young bachelor

and the older Cooke stayed in touch, however, and by 1854 Patton had married

Cooke’s daughter, Frances Mary. Not wanting her daughter living far away in

another city, the younger Pattons moved in with Mary’s family and they all

lived together in Salem for the rest of their lives.[xxvii]

The senior

Cooke purchased a book and stationery store on State Street in Salem in the

1870s, and 40 years later when his grandsons wanted to jump onto the postcard craze

band wagon, they opened the Patton’s Post Card Hall adjacent to it. A reported

5,000 postcards hung in brackets on the walls of the Hall - apparently the

largest postcard store in the northwest at the time.[xxviii, p.5 and xxviiib]

Patton’s Post Card Hall in

Salem [xxix]

Nellie and

Alick probably bought the card at a local store – orders could be made through

the upper floor mail-order office.

By 1928 Alick

owned a relatively small farm in the Willamette Valley on Wapato Creek near

Flett Road just south of Gaston. This was part of the land that John Flett had

settled on and received the patent for in October 1863. Steele farmed that

land, raised a family of 5 girls and (finally!) two boys. They built a family

home and eventually their son, George, would live in a smaller house on the

property with his sister, Gladys. In the early 1970s, my family and I would

visit Alick, George, and Gladys in that smaller house on the farm. After 1973,

only George and Gladys were left– Uncle Alick then resting in the

Yamhill-Carlton Pioneer Cemetery - he died at the age of 90. My sister and I remember those family visits

with much happiness and love. We became farm kids for a few days, milking cows,

collecting eggs, being a little freer to roam about and get dirty, and chumming

with distant cousins. Very formative times for a child.

I could

never have imagined, while playing in the hay bales at Uncle George and Aunty

Gladys’ farm, that I would spend October 17, 2019, 156 years to the day after

Abraham Lincoln signed that land patent, writing about the history of that land

and the people tied to it by papers and a postcard.

Bibliography

Green,

Virginia

Nemerov,

Alexander

Perry,

Leslie

1896 Appeals to Lincoln’s Clemency. The Century

Illustrated Monthly Magazine Volume 59, New Series Volume 29. Macmillan and Co.

London.