The two Banffs I grew up knowing were the 20,000 square kilometre Banff National Park in Alberta, Canada, and the town of Banff within it. I've driven through the park more times than I can count - I consider it part of my backyard. Named after the town in Scotland, and now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, it has grown into one of the major tourist attractions in Canada with an annual visitation of over 4 million people and a population of around 7500. It is one of the most beautiful places in the world.

Moraine Lake in Banff National Park.

Photo by Florian Fuchs.

I always imagined that to have such a place named after it, Banff must be a large city in Scotland and maybe have some mountains. But by North American standards, there are no really large cities in Scotland, and the mountains are in the Highlands. Glasgow is the largest city in the country with a population of nearly 600,000.

Banff, Scotland, in contrast to my expectations, is a very small northeastern town of about 3800 people situated on Banff Bay on the North Sea. I've previously posted about a postcard from

Scotstown, a small area in the west part of Banff. History, however, does not rely on the size of a community, and the original Banff has an intriguing past. As I've come to learn, my family has roots pretty deep into in that area.

According to

Wikipedia, Banff's first castle was built to repel Viking invaders (who did most of their Scottish plundering in the 6-9th centuries). My Ancestry DNA results show a 2% Norwegian and 1% Swedish connection at this time. Looks like a Viking or two might have slipped in there WAY back. By 1163AD, Malcolm IV was living at that castle in Banff and 101 years later the first recorded Sheriff of Banff in 1264 was Richard De Strathwan. Robert the Bruce bestowed a chapel to the Carmelite Friars and confirmed it to them in 1324 along with the land for the erection of a church and monastery just to the south of the community. In 1372 Banff was granted Royal Burgh status by the grandson of Robert the Bruce: King Robert II - who was the first Stewart monarch. Banff, along with Aberdeen and Montrose, was one of three major exporter of salmon to the continent of Europe by the 15th century.

Banff is situated to the north and west of the River Deveron (previously known as Dovern) which divides Banff from Macduff and flows into the north sea. A successful bridge crossed the river in 1779 after the first one failed in a flood. Upriver from that bridge, in a forested area where the river turns south, is situated Hospital Island, and on the north side of the island is an old weir. It is at that spot that the Mill of Banff used to stand.

William Robertson (one of my 4x great-grandfathers) was a distiller at the Mill of Banff Distillery (which existed from 1826 to 1863). This is well documented on at least two of his children's birth records, the 1841 census:

and in a notation in The Annals of Banff (1893) by William Cramond, referring to a grave marker in the Old Church yard in Banff:

Here's the actual headstone:

Photo courtesy of the Banff Preservation and Heritage Society

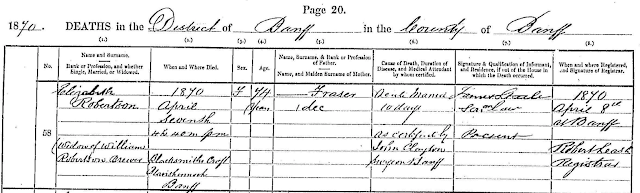

The Elizabeth referred to on the grave marker is the same one on this death record from 1870:

You'll note that

(1) Elizabeth Robertson was born a Fraser,

(2) she was the widow of William Robertson (brewer / distiller / vintner) and

(3) she died at the

Blacksmith Croft at Blairshinnoch Banff, which I have discussed in length before - this was where my 3x great grandmother (Grace Fraser Robertson) and 3x great grandfather (James Steele) lived and where James and his son, Alexander Milne Steele were both blacksmiths. These documents come together in irrefutable proof that these documents are all discussing the same woman.

To sum up: Elizabeth Fraser and her husband William Robertson ended up at the Mill of Banff Distillery by at least 1828 and were still there when William died in 1843 (and I can rightly claim that a drop or two of whisky runs through my veins).

Earlier, in 1824, on Grace Fraser Robertson's birth record, we see that Elspet and William had been living at or near Brackla as that this is where Grace was born (the birth recorded in Cawdor).

"Grace Fraser Daughter to William Robertson at Brackla and Elspet Fraser his wife was born the 23 of April and baptised the 8th of May 1824. Witnesses Mr. Alexr Fraser and John MacLean Excise officer there". The Fraser name was important at Brackla as what would become the Royal Brackla Distillery was started by Captain William Fraser in 1812. I am trying to find out if and how Elspet was related to the Captain. Brackla was the first distillery to be given the Royal monicker and is still in operation as part of Dewars. It was built on the estate of Cawdor Castle.

Here it was in ca. 1870:

It would appear from Grace's birth record that the family was either living at Brackla in 1824, or they lived nearby and Elizabeth had travelled to the big house for the birth. They are tightly tied to the nearby parish of Ardclach as that is where William and Elizabeth married and baptized several of their children. But since William Robertson was a distiller, he may well have been working at Brackla before getting the opportunity at the Mill of Banff Distillery.

To remind you, by 1841, William, Elizabeth, their daughter Ann (20) and 4 other children are living at the Mill of Banff. The Mill of Banff is elusive on maps - I haven't found one yet that records its location. The first mention of it I found at Scotlandsplaces is in relation to St. Mary's Well (according to the

1867-1869 Ordnance survey name books, Banffshire, Volume 3 / OS1/4/3/87) which was "... in the grounds of Duff House, Situated near the river Deveron, South of the Mausoleum and near to where the Mill of Banff Stood. It is said to be a Holy Well." Also noted in the Annals of Banff (1893, p3), The "... convent stood on Dovern at Miln of Banf in Banf parish."

St. Mary's Well is on the property of the Duff House. It is west of the golf course that is there now, and to the northwest of the big bend in the river.

The main structure on this small property now is the Duff Mausoleum (directly SE of the turquoise-y fields in the upper middle of the image - one can barely see a white dot which is the roof of the mausoleum).

If you look at the Ordnance map from 1866, you can see the area's history up to that time - in place names alone.

You'll note the Mausaleum is on the site of St. Mary's Chapel. St. Mary's Well is also there. According to the Canmore National Record of the Historic Environment, the first documentation of this site was in 1321 when as mentioned above, Robert the Bruce bestowed a chapel to the Carmelite Friars (note Mount Carmel beside Bachlaw Bridge, too).

So, the Carmelite Friars used it, a holy well is located there, the Mausoleum for the Duff house is there, a hospital was probably established during some epidemic on the land. And a Mill and Distillery lived there.

What is odd, though, is that i

n 1574, James VI granted the lands, buildings and revenues from this land to King's College in Aberdeen (all listed at Canmore under "Duff House Mausoleum"). The Mill of Banff Distillery would have paid taxes on this land that would have ended up at King's College.

Oddly enough, the only Aberdeen postcard in my collection is of King's College - a simple postcard to Gladys McCurrach - a 5-year-old girl who (in her whole life) had no idea that her ancestors helped pay to keep the place running.